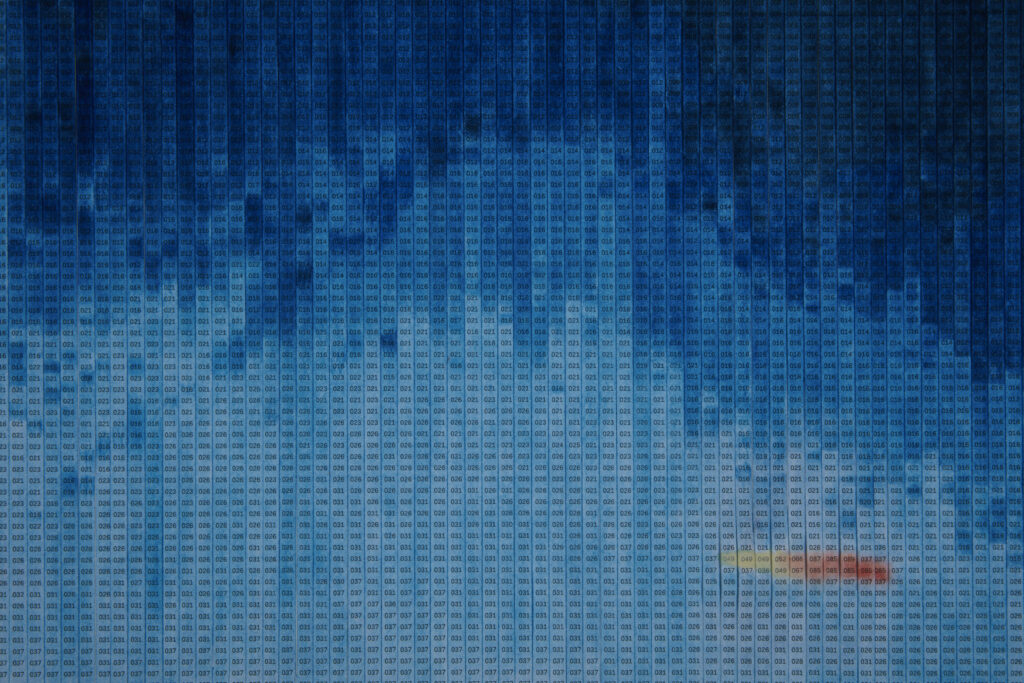

30th January 1980 – 12th October 2014

2016

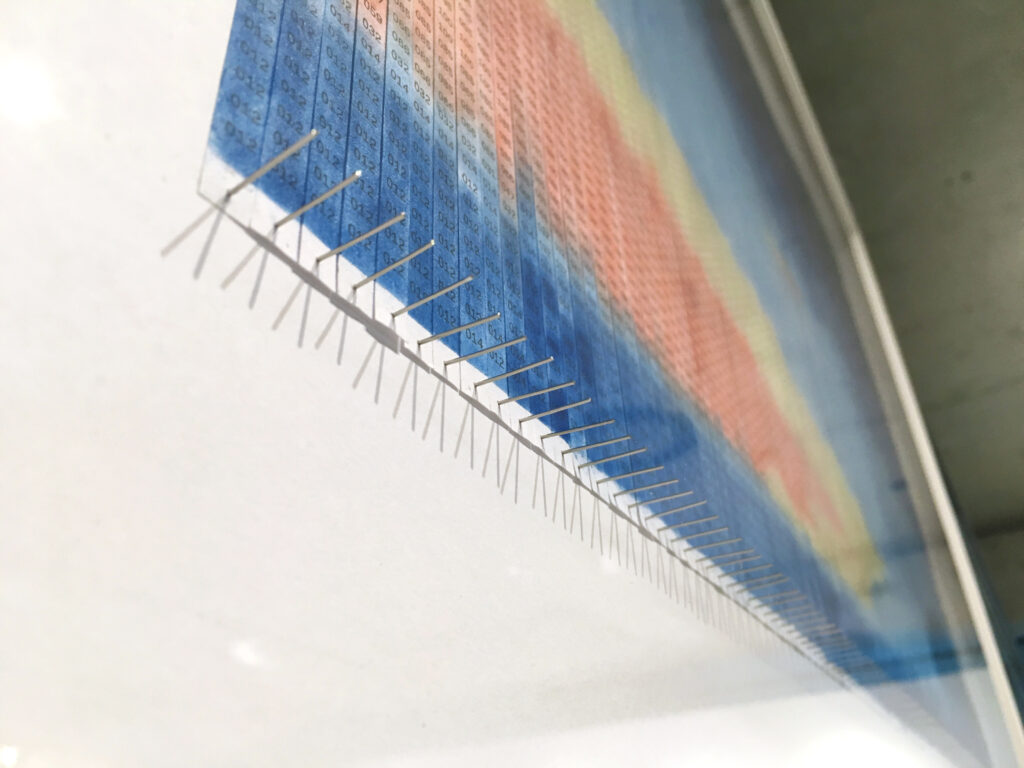

Print on paper, mixed media 83.5 x 111 x 4.5 cm

The last image of Kosmos 1154, is a reenactment of the first close-up TV image of Mars as done by the scientists of NASA in 1964. With an eagerness to test the validity of their data, and impatience in regards to computer data calculation, they decided to use a real-time data translator machine to convert a Mariner 4 digital image data into numbers printed on strips of paper. With the contemporary context of witnessing the re-entry into space of Russian rocket Kosmos 1154 launched in January 1980, the work reenacts a similar making, yet reverse the process of revealing an image through the slow process of drawing according to the brightness values of the last image of the rocket bursting into flames on the evening of the 12th of October 2014 in the sky of Svalbard.

“The theme of translation is taken up again, this time with reference to Maridet’s surprise witness to the re-entry of rocket debris from the Russian (formerly Soviet) intelligence satellite Kosmos 1154 into the Earth’s atmosphere, after almost 35 years in orbit. Although members of Maridet’s expedition were able to capture some snapshots of the flaming object across the sky of Svalbard, he has chosen not to show any of these images directly, but to further mingle his re-telling of the event with a story from the opposite spectrum of the Cold War Space Race.

By mid-July 1965, the Mariner 4 spacecraft had successfully beamed back to NASA data containing the first close-up images of Mars. Whilst waiting for the computer processed images, communications engineers used a “real-time data translator” to convert raw pixel information into a numerical print out, which was then hand coloured like a paint-by-numbers drawing. Maridet has used a similar technique to produce his own hand-drawn record of the Kosmos re-entry, converting pixel information from a digital photo into numerical brightness values.

In an era where the rising ubiquity of the photographic image has come to supersede the uniqueness of direct-lived experience, perhaps some solace might be found in such playful historical reversals. By taking us back to this moment in 1965, a time when the hand-drawn still maintained the upper-hand over snail-paced computer processors, Maridet’s melancholic identification with the past becomes a negative stand-in for what has become lost in the present; revealing layer upon layer of absence and obsolescence, that is to say, progress.”

(Nadim Abbas, Blindspot Gallery exhibition catalogue, 2016)